On Books and Belonging

Long ago, I read the following words in Kahlil Gibran’s “Our Children”:

“Your children are not your children. They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you yet they belong not to you.”

So it is with books as well as children: the sense that the writing comes through me more than from me, that my words are stories longing to tell themselves. And that they, like children, must inevitably leave me and be released to the wide world.

Two meanings of the word ‘belong’:

1) to be the property of

2) to be a part of

When the Ocean Flies explores ‘belonging’ in both senses of the word. Firstly, the exchange of a child from one set of parents to another, as happens in adoption, wherein the child no longer belongs (as in Gibran’s meaning, like property) to the parents who created her. The book also explores the deep yearning to ‘belong’ in the other sense of the word.

Part of releasing books (or children) into the world is to hope that they find others to whom they belong, as in the second meaning. And as any parent, author, artist, or anyone who has ever released anything into the world knows, there is the yearning for affirmation of that kind of belonging for those we love.

With children, a text or a phone call home to say they’ve found their people offers that kind of affirmation. With books, reviews are the primary demonstration that the story has found its people.

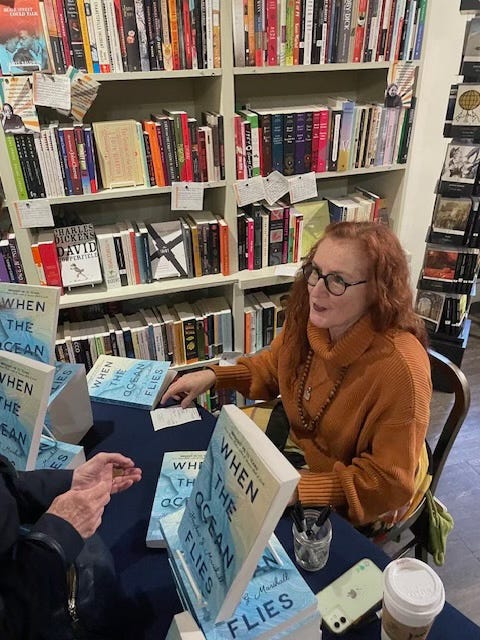

It’s now a little over a month since I released When the Ocean Flies into the world. I mentioned in my last post that, “my hope, in addition to the obvious one—that the novel resonates and that Alison, Eilidh, Vic and Mary find places in readers’ hearts—is that in some way, this book is the heavy machinery that opens a space for others to claim their truth.”

Reviews are beginning to come in on Amazon and Goodreads offering affirmation that the novel is, indeed, finding its people:

“You had me from that passage on page 8 and the first paragraph on page 9. I too, have known the ‘strangeness of having another name’ and ‘the immensity of knowing HER name.’ Thank you for putting these words to page. It is so incredibly validating… You know how sometimes when you're out and about and you just wish you could be home reading your book? That's how I felt about When the Ocean Flies. Well done, you!” –Michelle G.

“As an adult adoptee who has carried the wounds of adoption and gone through the process of healing through searching, this book resonated deeply with me. Although a novel, it feels like the author, also an adoptee, has clearly poured her own experiences and insights into this work.

On the surface it is a well written story following Alison, a newly single 50 year old mother of grown-up children, returning from her home in the United States to her birthplace in the islands of Scotland to attend the funeral of her birth father who she has grown close to since finding him six years earlier.

Throughout the story, the author skilfully weaves past memories into present time feelings, filling in a life story from growing up as the adopted child of inadequate parents, through many years pleasing a controlling husband, and along the way denial of a relationship that went against societal norms. Eloquently written sentences provide insights into Alison’s desperate need to please in order to retain relationships and friendships however unsuitable or damaging they may be, subsuming her own needs through fear and a sense of unworthiness all too common to adoptees.

‘I spent rainy afternoons sketching my dreams, though the dreams were nightmares born of insecurity and a sense of displacement and loss’

‘Whenever anyone walked away, I trembled as though I might disintegrate’

and

‘My adult self doesn’t want to be anyone’s rescue case. My child self has wanted someone to come for her since the very beginning’

These words express feelings I have known so well but could never have expressed so perfectly. Even her husband’s icy disdain for her need to search echoes my own experience.

Of her birth mother Alison ponders ‘Once, she’d curled within that body, known every gurgle for forty weeks, their two hearts beating. The rhythms of her mother’s footfalls, the melody of her voice, the drumroll of her tears, the burble of laughter.’

The author shows us the pain on all three sides of the ‘Adoption Triad’ and the healing power of reunion, of understanding one’s roots and eventually finding the courage to be yourself and live the right life. She also conveys the loss of so many years with birth parents that can never be regained and the sense that nobody else would really understand.

I needed to read the book twice to absorb it all.

In my view, this book is must read for every adult adoptee. For everyone else, it is an intriguing story filled with insights, emotions, discovery, travel and a touch of history.” –Rose

In addition to allowing me a window into how When the Ocean Flies is doing out in the world, these reviews create a sense belonging between us all—author, reader, book, humans seeking belonging in the wide world—and for that I am deeply grateful.

If you’ve read When the Ocean Flies and it has resonated with you in some way, I’d be grateful if you’d leave a review. It doesn’t have to be long or eloquent—just a wee note to say what you liked and to help others find it.